Progress Report #2

One month has passed since the last progress report, and I'm back with another one. Most of this month's effort went into accuracy and performance improvements of the pixel processing unit (PPU). Its main purpose is converting data stored in memory like VRAM and object attribute memory (OAM) into pixels on the screen.

Rendering Engine

Let's begin with the most interesting thing I've done during the last month: a rewrite of the rendering engine. The Game Boy Advance can use up to four different backgrounds and an object layer. Each background and object has its own priority which determines the drawing order. Backgrounds with high priority are drawn in front of backgrounds with low priority. Transparent areas inside backgrounds are used to display the background with the next highest priority.

When talking about the rendering engine, I mean the part of the emulator that combines the different layers into the final scene shown on the screen. Its name changed several times during development and ended up being called collapse.

renderObjects();

switch (mmio.dispcnt.mode) {

case 1:

renderBg(&PPU::renderBgMode0, 0);

renderBg(&PPU::renderBgMode0, 1);

renderBg(&PPU::renderBgMode2, 2);

collapse(0, 3);

break;

// ...

}

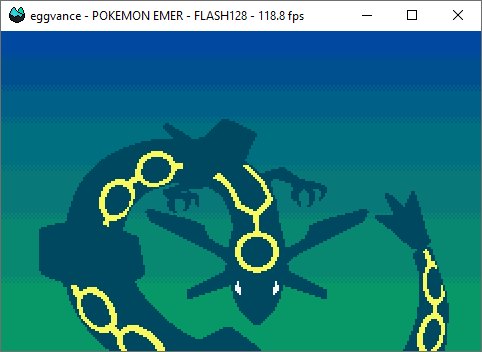

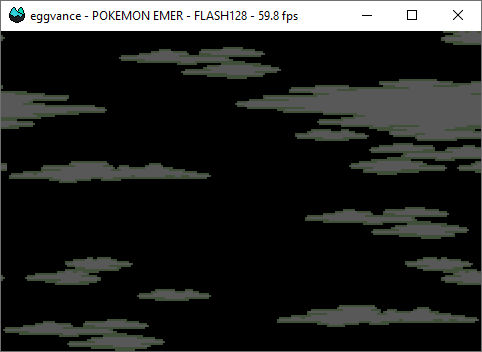

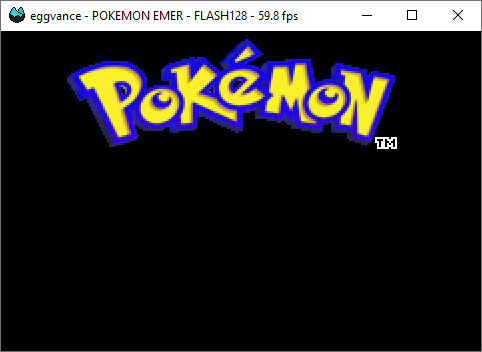

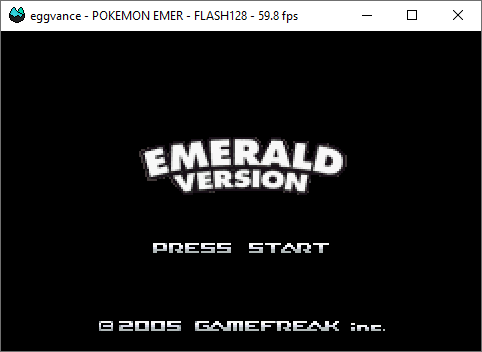

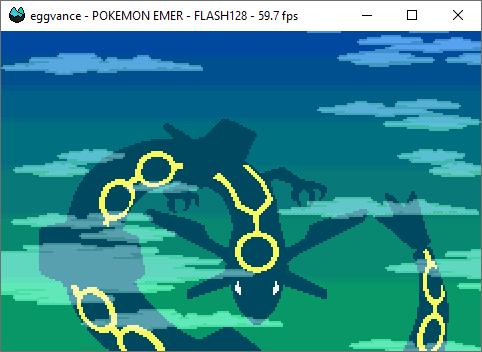

The code above shows the parts of the PPU that take part in rendering the Pokémon Emerald title screen. The used backgrounds and their render function are dependent on the selected video mode in the DISPCNT register. You can see the resulting individual layers in the following images.

Background layer 0

Background layer 1

Background layer 2

Object layer

One of the most challenging aspects of emulating the PPU is combining the layers into the final scene. That's what the collapse function is doing. The process itself is rather straightforward for simple scenes. Just loop over the layers from highest to lowest priority and use the first opaque pixel you find. It gets much harder when dealing with effects like windows and color blending, which need to look at multiple layers at the same time.

Blending backgrounds 0 and 1

Final scene

The predecessor of the collapse function consumed a sizable amount of CPU time and was a prime candidate to be reworked. The new version makes heavy use of C++ templates and has improved performance by around 35%. It also fixed several bugs that were related to object windows.

Forced Blank

Even though the GBA uses an LCD, its hardware behaves more like a CRT. In those displays, the electron beam has to move to the start of the next line after finishing the previous one. This period is called horizontal blank (H-Blank). Once the whole frame has been drawn, the beam must return to the beginning of the frame. This is called vertical blank (V-Blank).

Most of the game logic and graphics processing takes place during the blanking intervals because they don't interfere with scanline drawing. Another reason is the fact that access to video memory outside of the blanking intervals is either restricted or has negative side effects, like reducing the total number of displayable objects. These restrictions can be lifted by setting the "forced blank" bit in the DISPCNT register, which causes a white line to be displayed. There isn't much to do emulation-wise apart from filling the current scanline with white pixels.

if (mmio.dispcnt.force_blank) {

u32* scanline = &backend.buffer[WIDTH * mmio.vcount];

std::fill_n(scanline, WIDTH, 0xFFFF'FFFF);

return;

}

Color Encoding

The Game Boy Advance uses one 16-bit halfword to encode colors in the BGR555 format. That effectively wastes one bit, but that doesn't seem to be a problem. Modern 16-bit color formats like RGB565 tend to use that extra bit for more green values because the human eye can distinguish shades of green the easiest.

I'm using SDL2 for video, audio and user input. It allows the creation of textures in the desired BGR555 format, which are then used for hardware-accelerated rendering. The only problem with this approach is the fact that modern hardware tends to use ARGB8888, which causes SDL to convert the whole frame from one format to the other. Removing this implicit conversion by converting the colors myself resulted in a 10 to 15% performance increase.

u32 PPU::argb(u16 color) {

return 0xFF000000 // Alpha

| (color & (0x1F << 0)) << 19 // Red

| (color & (0x1F << 5)) << 6 // Green

| (color & (0x1F << 10)) >> 7; // Blue

}

High-Resolution Clock

Timing an emulator can be quite hard. If the frame has been rendered early, there isn't much you can do aside from waiting. The GBA has a refresh rate of 59.737 Hz, 280,896 cycles per frame on a 16.78 MHz CPU. The ideal frame time for this scenario is 16.74 ms.

Using components from the C++ STL would result in inaccuracies that accumulate over time. Luckily I found an answer on Stack Overflow which solves this problem with platform-specific code. Using this as a base for the high-resolution clock in my emulator resulted in consistent frame rates which tend to stay in the range of 59.7 to 59.8 frames per second all the time.

Final Words

Aside from the things talked about in this progress report, there were many minor bug fixes and accuracy improvements. The emulator's overall performance increased by quite a bit. My next goal is to create the first release version with compiled Windows binaries. That also means adding a config file and fixing bugs in several games.